This week I picked up Dance Dance Revolution by Cathy Park Hong from my local public library. The title attracted me initially; I expected some wry commentary on pop culture, some autobiographical poems. The usual. And, if you already know anything about the book, you'll know I was quite surprised when I opened it and started reading.

Rather than the realistic mode of poetry I've been surrounded by recently, this collection is a work of imagination and fancy. There are two main speakers in the book: the Desert Guide and the Historian. The Desert Guide speaks in an amalgam of pidgin languages, and the Historian transcribes this speech, and every so often, interjects with some interpretation in standard English. The result is fascinating and quite different from anything I've read recently. The closest comparison I could make would be to Rushdie's Haroun and the Sea of Stories, which would be classified as fiction, of course, but both books have the same fanciful play of language working to drive the story. Since I am still in the middle of reading both books, I can't make any firm conclusions. But I plan to report back next time with a review.

In the meantime, here is a sample from the beginning of Dance Dance Revolution:

3. The Fountain Outside the Arboretum

Ahoy! Whitening wadder fountain. Drink. Afta cuppa-ful

o aqua vitae, yo pissin fang transfomate to puh'ly whites

like Bollywood actress swole en saffron,

flashim her tarta molar to she coquetry man.

So musical! So suggestive. I am entranced. More soon.

-- Jill

Welcome to new contributor Angela Elles, who joins Jill Koren and Matthew Vetter for dialogue about poetry, events in the community, interviews, book reviews and more. Lend your voice to the discussion.

Monday, December 15, 2008

Monday, December 8, 2008

Anne Finch

Dear Readers,

This week I’m doing some research on the English poet Anne Finch (1661-1720). Here is one of my favorites by her, “Glass.”

Glass

O Man! what Inspiration was thy Guide,

Who taught thee Light and Air thus to divide;

To let in all the useful Beams of Day,

Yet force, as subtil Winds, without thy Shash to stay;

T'extract from Embers by a strange Device,

Then polish fair these Flakes of solid Ice;

Which, silver'd o'er, redouble all in place,

And give thee back thy well or ill-complexion'd Face.

To Vessels blown exceed the gloomy Bowl,

Which did the Wine's full excellence controul,

These shew the Body, whilst you taste the Soul.

Its colour sparkles Motion, lets thee see,

Tho' yet th' Excess the Preacher warns to flee,

Lest Men at length as clearly spy through Thee.

“Glass” is an intense observation and meditation on the invention and numerous forms of glass. It is written in heroic couplets, but is also sonnet-length, having 14 lines. The speaker considers the window, the mirror, and the wine-bowl in laudatory terms. But what begins as praise and admiration, becomes a warning in the final two lines, “Tho’ yet th’ Excess the Preacher warns to flee, / Lest Men at length as clearly spy through Thee.” (l. 13-14)

To speak in less than formal terms, I was really blown away by this poem. I think it has something to do with the element of surprise at work in the final two lines, a late volta, or turn. It seems very, very contemporary. There’s a slight ambiguity at work here, as well. A reader familiar with even a small portion of Finch’s work (as I am) would expect commentary on gender issues, and the poem accomplishes that. The sonnet length, the function of glass as a mirror, and the general admonition in the final two lines are representative of the speaker’s warning to women’s excesses of vanity. However, the same admonition can also be indicative of the excess of wine, something somewhat more particular to men. The poem functions on multiple levels and achieves a multiple levels of success. But what is particularly fascinating to me, is that it achieves all this without a single allusion, the trope du jour employed so heavily by the male poets in this time period. Enjoy!

-Matthew

This week I’m doing some research on the English poet Anne Finch (1661-1720). Here is one of my favorites by her, “Glass.”

Glass

O Man! what Inspiration was thy Guide,

Who taught thee Light and Air thus to divide;

To let in all the useful Beams of Day,

Yet force, as subtil Winds, without thy Shash to stay;

T'extract from Embers by a strange Device,

Then polish fair these Flakes of solid Ice;

Which, silver'd o'er, redouble all in place,

And give thee back thy well or ill-complexion'd Face.

To Vessels blown exceed the gloomy Bowl,

Which did the Wine's full excellence controul,

These shew the Body, whilst you taste the Soul.

Its colour sparkles Motion, lets thee see,

Tho' yet th' Excess the Preacher warns to flee,

Lest Men at length as clearly spy through Thee.

“Glass” is an intense observation and meditation on the invention and numerous forms of glass. It is written in heroic couplets, but is also sonnet-length, having 14 lines. The speaker considers the window, the mirror, and the wine-bowl in laudatory terms. But what begins as praise and admiration, becomes a warning in the final two lines, “Tho’ yet th’ Excess the Preacher warns to flee, / Lest Men at length as clearly spy through Thee.” (l. 13-14)

To speak in less than formal terms, I was really blown away by this poem. I think it has something to do with the element of surprise at work in the final two lines, a late volta, or turn. It seems very, very contemporary. There’s a slight ambiguity at work here, as well. A reader familiar with even a small portion of Finch’s work (as I am) would expect commentary on gender issues, and the poem accomplishes that. The sonnet length, the function of glass as a mirror, and the general admonition in the final two lines are representative of the speaker’s warning to women’s excesses of vanity. However, the same admonition can also be indicative of the excess of wine, something somewhat more particular to men. The poem functions on multiple levels and achieves a multiple levels of success. But what is particularly fascinating to me, is that it achieves all this without a single allusion, the trope du jour employed so heavily by the male poets in this time period. Enjoy!

-Matthew

Monday, December 1, 2008

What is the poet trying to say?

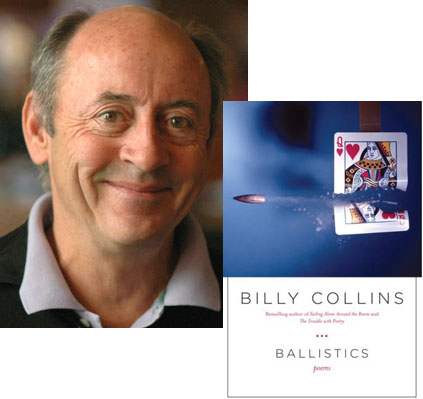

Yesterday, I stumbled upon "Effort" by Billy Collins in his new collection Ballistics. My uncle, Tom, had left the book lying on a table at my grandfather's house, so I picked it up and the pages fell open to "Effort." Collins's style always makes me feel as though the poet has sidled up to me at a family gathering to tell me an important (and well-composed) secret, and this time was no different.

(Disclaimer: I'm working from memory here, so please forgive me if I resort to paraphrase) The poem opens with a gentle rant against those teachers who always asked the question mentioned in the title. The speaker then gives us the comical image of Emily Dickinson chewing her pen, looking out the window, trying to figure out what to say. The rant resonates with me now especially because, as I am teaching a mixed-genre workshop here in my community, I often find myself in the position of having to either field this exact question, or listen to the not-so-gentle rants against my students' past teachers who pestered to death any potential love they may have had for poetry with said question.

Collins whispers slyly to the reader: It's okay not to know. And besides, you can relieve yourself of the responsibility of being the authority. The poem then turns cleverly to the speaker's own poetic subject. In letting his readers off the hook, Collins also excuses himself from having to make something with "absolute" meaning. He talks of absence, describes the night. And leaves it to future generations and future ruler-tapping high school teachers to figure out what it is he's been trying to say.

I appreciate the humor and candor in this poem, as well as the characteristic Collins humility that so incredibly accompanies such lovely language and elegant lines. I look forward to reading the rest of his new collection.

News of the submission slog: I am receiving rejections weekly, if not daily, these days. This at least proves I am doing the work of getting my poems out there. And most of my recent ones have been more than the one word, "No" that I once received by email. Can't say that I'd be unhappy to have an acceptance or two thrown into the mix. But I'll continue to slog on. Next targets: Beloit Poetry Journal and Minnetonka Review.

Happy December!

-- Jill

Monday, November 24, 2008

Poetic Doubt in Larissa Szpurlok’s Embryos & Idiots: Some (Rambling) Thoughts on Book 1; Submission News; Thanksgiving Poem

Hello Readers!

The complex association and allegory at work in Szpurlok's Embryos & Idiots is, at first glance, somewhat confounding. I am troubled, if that is the right word, because I cannot immediately obtain linear meaning. However, as I read and re-read, as I immerse myself in the sounds and semantics of the language, it becomes apparent that Szpurlok's collection avoids denotation (and celebrates its own associative and connotative systems) as a means to challenge the linear and representational modes of the myths the collection delights in undermining. Szpurlock's production of a mythic narrative (and her dissolution of that narrative) is a feminist critique of and response to the phallo-centric and patriarchic myths of Genesis and Paradise Lost. While this assignment places the collection in the realm of the public manifesta, the collection operates in the private sphere as well. In a number of instances in Book 1, the speaker breaks away from the allegorical narrative to question her audience. These questions represent an ongoing rhetorical trope of what seems to be poetic doubt. In the final line of "Boulders," the speaker asks "This Century wants anything. Is that a soul?" In "Idol": "Anoton spilled the secret- wouldn't we all to get what we want?" In "Reaper,"Does it matter what we're made of?" In "Passive-Aggressive Music": "and what's so important that it makes / you forget, like ammonia, everything? In "Naves and Navels," "Does anyone know? We who are old and full of words?" These types of questions are rampant in the first section of Embryos & Idiots and they are significant because they represent Szporluk's doubt yes, but also her need to validate her (anti-)myth (non)narrative. Her readers, it seems, have a crucial role to play in this process. Everyone else is either an Embryo or an Idiot.

In other news, I’m preparing submissions to American Poetry Review and New Ohio Review. I hope everyone is fortunate enough to be spending time with family and friends this week. Check out this Thanksgiving poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar to get into the holiday spirit. My favorite is: “Oomph! dat bird do' know whut's comin'; /Ef he did he'd shet his mouf.” Happy Thanksgiving!

-Matt

The complex association and allegory at work in Szpurlok's Embryos & Idiots is, at first glance, somewhat confounding. I am troubled, if that is the right word, because I cannot immediately obtain linear meaning. However, as I read and re-read, as I immerse myself in the sounds and semantics of the language, it becomes apparent that Szpurlok's collection avoids denotation (and celebrates its own associative and connotative systems) as a means to challenge the linear and representational modes of the myths the collection delights in undermining. Szpurlock's production of a mythic narrative (and her dissolution of that narrative) is a feminist critique of and response to the phallo-centric and patriarchic myths of Genesis and Paradise Lost. While this assignment places the collection in the realm of the public manifesta, the collection operates in the private sphere as well. In a number of instances in Book 1, the speaker breaks away from the allegorical narrative to question her audience. These questions represent an ongoing rhetorical trope of what seems to be poetic doubt. In the final line of "Boulders," the speaker asks "This Century wants anything. Is that a soul?" In "Idol": "Anoton spilled the secret- wouldn't we all to get what we want?" In "Reaper,"Does it matter what we're made of?" In "Passive-Aggressive Music": "and what's so important that it makes / you forget, like ammonia, everything? In "Naves and Navels," "Does anyone know? We who are old and full of words?" These types of questions are rampant in the first section of Embryos & Idiots and they are significant because they represent Szporluk's doubt yes, but also her need to validate her (anti-)myth (non)narrative. Her readers, it seems, have a crucial role to play in this process. Everyone else is either an Embryo or an Idiot.

In other news, I’m preparing submissions to American Poetry Review and New Ohio Review. I hope everyone is fortunate enough to be spending time with family and friends this week. Check out this Thanksgiving poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar to get into the holiday spirit. My favorite is: “Oomph! dat bird do' know whut's comin'; /Ef he did he'd shet his mouf.” Happy Thanksgiving!

-Matt

Monday, November 17, 2008

Sharon Olds: "The Clasp"

To pick up on Matt's themes of writing on the experience of living with children as well as his most recent theme of violence coexisting with beautiful restraint, I would like to offer Sharon Olds's "The Clasp." It contains perfectly within one small stanza the complex ambivalence of parental love.

To pick up on Matt's themes of writing on the experience of living with children as well as his most recent theme of violence coexisting with beautiful restraint, I would like to offer Sharon Olds's "The Clasp." It contains perfectly within one small stanza the complex ambivalence of parental love.It begins with a swinging, back-and-forth rhythm: "She was four, he was one, it was raining, we had colds," (1). The rocking syntax of the four quick phrases helps the speaker lay out the facts of the situation while drawing the reader's ear and body into the music of the line. The following line relaxes into a longer clause, though it still resists a full stop: "we had been in the apartment two weeks straight," (2). The reader quickly understands that this lyric will be a confession and prepares to be sympathetic. Anyone, parent or not, who has spent five minutes with children can immediately see the inherent tension in the set up. The narrative then moves to the central action: the mother-speaker grabs the wrist of the older child to "keep her from shoving him over onto his / face, again"-- a perfectly understandable move (3-4)..

The real drama, however, occurs in less than a second, when the mother squeezes her daughter's wrist "to make an impression on her" (6); she reports savoring the stinging sensation, the "expression, into her, of my anger" (9). But the poem shifts again, from the "righteous chant" and staccato rhythms-- grab crush release-- to the parent observing her child experiencing her own revelation: "she learned me. This was her mother, one of the / two whom she loved most, the two / who loved her the most, near the source of love" (19-21). The intimate, innocent mother-daughter relationship deepens a level to envelop something dark. The mother watching the child learn this allows the reader to be present at the moment of the mother's realization. They hurtle together closer to the "source of love," and find "this"-- the speaker refers to the anger only with a pronoun, for the word anger cannot contain all of what "this" stands for: the moment, the learning of something big about the world from a child, the violence, the perverse enjoyment of it, the protecting of one child at the expense of another, and all the subtleties of emotion that occur in a moment of intense loving.

The exercise of writing this post reminds me of the frustration inherent in trying to "explain" a poem. So I recommend you find the poem, read it, and experience the "this" for yourself. I found it in Not For Mothers Only, which I am still reading with pleasure. You can find the full text on the web at http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-clasp/.

-- Jill

Monday, November 10, 2008

Some Thoughts on “Winter Mix” and “Chaos Theory,” from Carol Ann Davis’ Psalm

Lately, I’ve been reading Carol Ann Davis' Psalm, a collection of poems which explores, among other things, the speaker’s grief at the death of her father.

These poems are at once intensely violent and beautifully restrained. One of my favorites from the collection is "Winter Mix," which begins, "This is a day with ghosts in it, / with husks and some kind of confession at its heart." These lines serve to introduce the poem, as well as the scene. The reader is lead to the next couplet expecting these ghosts, expecting a confession. The ghosts, it seems are represented in the speaker’s meditation on her dead father's photograph: "One day I won't wake up to my father's portrait. / I'll take it and put it / in the sitting room / and it will become small to me." The speaker's prediction that she will overcome her grief is followed by the confession that this will not happen for some time. In the final lines of the poem, the speaker describes the power of the photograph, and the power of her father to transport and transform her "into cumulus and cirrus, / into ganglia and spine, / into zephyrs and waves." This seems to be the most powerful moment of the poem. By contemplating her father's death, the speaker envisions her own "death," her metamorphosis into something utterly non-human. But it is a metamorphosis she admits she is unprepared for when she confesses in the final two lines: "I'm sorry / to come with empty hands."

Another favorite is "Chaos Theory." Highly abstract and experimental, "Chaos Theory" consists of a number of anaphoric, one-line stanzas gathered together under the unified banner of "Chaos Theory," a highly complex mathematical theory, which attempts to explain the random behavior of systems which are defined as having deterministic properties. The theory is confusing, to say the least, but its complexity is indicative of the intricacy of the levels of narrative or non-narrative at work in the collection as a whole. I say narrative OR non-narrative to emphasize the irregular forces of voice, structure and meaning at work in the collection- all of which contribute to the total dissolution of narration taking place in Psalm. "Chaos Theory," while it is a beautiful and random poem in and of itself, acquires its meaning from the poems in the collection which surround it. It emphasizes the notion that the grief of a physical loss is also a metaphysical loss, a loss of meaning, a loss of language.

Hope everyone is well.

-Matthew

These poems are at once intensely violent and beautifully restrained. One of my favorites from the collection is "Winter Mix," which begins, "This is a day with ghosts in it, / with husks and some kind of confession at its heart." These lines serve to introduce the poem, as well as the scene. The reader is lead to the next couplet expecting these ghosts, expecting a confession. The ghosts, it seems are represented in the speaker’s meditation on her dead father's photograph: "One day I won't wake up to my father's portrait. / I'll take it and put it / in the sitting room / and it will become small to me." The speaker's prediction that she will overcome her grief is followed by the confession that this will not happen for some time. In the final lines of the poem, the speaker describes the power of the photograph, and the power of her father to transport and transform her "into cumulus and cirrus, / into ganglia and spine, / into zephyrs and waves." This seems to be the most powerful moment of the poem. By contemplating her father's death, the speaker envisions her own "death," her metamorphosis into something utterly non-human. But it is a metamorphosis she admits she is unprepared for when she confesses in the final two lines: "I'm sorry / to come with empty hands."

Another favorite is "Chaos Theory." Highly abstract and experimental, "Chaos Theory" consists of a number of anaphoric, one-line stanzas gathered together under the unified banner of "Chaos Theory," a highly complex mathematical theory, which attempts to explain the random behavior of systems which are defined as having deterministic properties. The theory is confusing, to say the least, but its complexity is indicative of the intricacy of the levels of narrative or non-narrative at work in the collection as a whole. I say narrative OR non-narrative to emphasize the irregular forces of voice, structure and meaning at work in the collection- all of which contribute to the total dissolution of narration taking place in Psalm. "Chaos Theory," while it is a beautiful and random poem in and of itself, acquires its meaning from the poems in the collection which surround it. It emphasizes the notion that the grief of a physical loss is also a metaphysical loss, a loss of meaning, a loss of language.

Hope everyone is well.

-Matthew

Monday, November 3, 2008

Visual Poetry II

As promised, here are the images from Eleni Sikelianos's poem, "Experiments with Minutes." Notice again how creation of the images spur the text, rather than the other way around. (Apologies for the quality of the pictures; I'm a poet, not a photographer.)

As promised, here are the images from Eleni Sikelianos's poem, "Experiments with Minutes." Notice again how creation of the images spur the text, rather than the other way around. (Apologies for the quality of the pictures; I'm a poet, not a photographer.)At Matt's suggestion, I delved into this month's issue of Poetry Magazine, and wow! I was overwhelmed by the variety and ingenuity of the visual poetry in this issue. Geof Huth's commentary on the works is fun and enlightening, too. He has written a longer article available online, too, at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/journal/feature.html?id=182397.

I'd love to talk about each poem, but for the sake of focusing, I'm going to choose Joel Lipman's excerpt from "Origins of Poetry" (to view the poem see http://www.poetryfoundation.org/archive/poem.html?id=182405). What appeals to me about this poem is the overlapping and interaction between the two texts: the "found" text of the old science book and Lipman's rubber stamp composition. Layering in this way mimics the way in which we are always composing on a palimpsest, one that is never completely erased. Each voice is merely a part in the chorus, and yet, Lipman's lines are clearly the soloist of this piece. Other graphic features-- squiggles, red dots-- also call attention to the artifice, which helps guide the reader's attention. The harmony parts, though, are still audible, and the sheer fun of writing a poem with a title as grandiose as "Origins of Poetry" on a tract about magnetism and electricity makes unimaginable connections possible. Perhaps the origins of poetry are as fundamental as the laws of magnetism. In this way, Lipman's poem aligns itself with the others in this issue: each one questions the origins, and in the process, the limits of language and poetry. A worthy experiment, whether you call it science or linguistics or art or all of the above.

Thanks to Matt for the tip! -- Jill

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)